Friendship Part Two

Strength, Vulnerability and the difference between male and female friendships

If you haven’t read part one on friendship you can find it here.

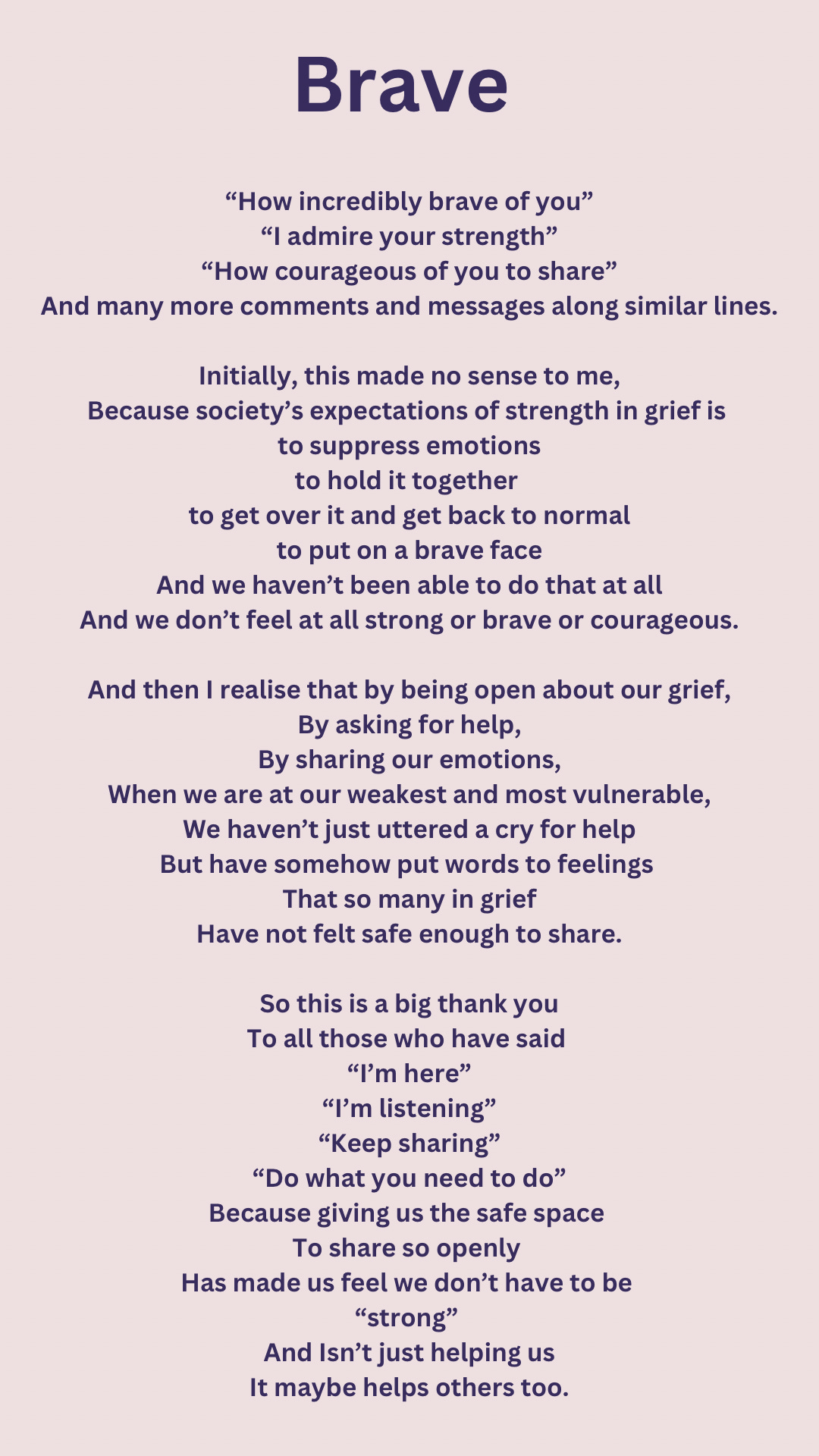

From my very early days of grief I have been open about sharing what I’ve been going through, whether this was face to face or virtually on my personal Facebook and Instagram accounts. Recently, I received a number of comments about my courage in sharing so openly after a talk I gave and it made me feel really odd. I have always felt uncomfortable with complements of this type because I have only been able to share so honestly because my friends gave me a space safe in which to do so. I wrote a poem about this three weeks after my daughter died, and it still encapsulates how I feel about this.

When Marisa Renee Lee was a guest on the We Can Do Hard Things podcast in July 2022 she talked about how she didn’t want to be complemented for her vulnerability in grief and said “I could fall all in because there were people and systems to catch me.” She explores those thoughts further in her book Grief Is Love: Living with Loss, considering the problem that the sense of safety that vulnerability requires is not equally distributed in society but that all grievers still have to find a way to access it. She writes;

Some people are too busy to be vulnerable. Some of us are too female, too poor, too gay, or too Black for vulnerability—there’s no space in our lives for it…. How do you begin to access the vulnerability that grief requires in the absence of safety and security? If day-to-day living often feels like a battle, grieving seems like a luxury…I’m here to tell you that when you’re grieving, vulnerability is no longer a choice; it is a matter of necessity. You cannot neglect your physical or mental health by pretending to be “fine” or “okay.”

The safety that vulnerability requires may not be equally distributed, but we have to find a way to access it in order to live with loss. To arrive at a place with our loss where, at a minimum, we have a handful of spaces, places, or people where we feel safe being vulnerable. You may need that sense of safety in order to tell the truth about the impact of your grief on your life. Sharing feelings that make us feel ashamed or embarrassed with others is hard. If you can’t speak it, write it out. Commit to sharing it, or at least some of it, with at least one other person. Your life, your health, and your heart depend on it.

While this is my space to write about my grief experience, and I won’t often refer to my husband or son, this is a rare post where it seems right to contrast my experience of friendship, grieving and vulnerability with that of my husband. While I don’t want to jump to conclusions based on such a tiny sample size, it is I think fair to suggest that the way in which females make and maintain friendships made it easier for me to be vulnerable in front of my friends. Our meet ups had previously involved lots of talk about feelings and difficult situations. Sharing and supporting each other through the inevitable ups and downs of life is just what my friends and I instinctively do, so it didn’t seem like a huge risk to the friendships to be open about how I was or wasn’t coping with grief.

My husband, however, had no idea which of his friends he could trust enough to let his guard down and show vulnerability without them feeling uncomfortable, and thus making him feel worse. In addition, we were both amazed to see and hear comments from some of his friends telling him to be strong, and that he needed to do so in order to support his family. These outdated concepts of what it means to be a man really got me angry and were so unhelpful considering all I know about the importance of expressing our feelings as an essential part of the grieving process and the dangers of just pretending to be ok. Thankfully, he did find that crucial “handful of spaces, places, or people where we feel safe being vulnerable” and has a couple of friends he meets up with on a regular basis to talk these things through, but it wasn’t as instinctive or quick as it was for me.

I haven’t yet red Billy No-mates: How I realised men have a friendship problem by Max Dickins, but after reading an interview with him in the Guardian on the 9th July 2022 I think this book addresses further some of the differences I am only starting to touch on here if any of you are interested in this topic.

He refers to research by Dr Robin Dunbar “Women tend to socialise face-to-face with a strong preference for one-to-one interactions, based around talk and intense emotional disclosure. Men, however, tend to socialise side-by-side, preferring to hang out in groups, where intimacy is demonstrated by doing stuff together – playing five-a-side, going fishing, climbing mountains and so on. For men then, activities are the main course of the social feast.” He continues;

Women put more effort into maintaining their friendships, while men are apt to let their social circle wilt and co-opt their partner’s instead. As the American standup John Mulaney has quipped: “Men don’t have friends. They have wives whose friends have husbands.” Men treat the women in their lives like their own personal HR department. If guys were honest, they’d introduce their better half at weddings with, “This is Claudia, my wife and director of people operations at Geoff Limited.”

And that circles back nicely to the “Friendship is a To-Do” philosophy from Laura Tremaine that I wrote about last week.

To finish I wanted to quickly share from The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise by Martín Prechtel, one of the first books about grief that I read. He argues that in grief, a tribe is necessary, but that in modern life for most people “there is no village, no tribe, no body of humans that constitute a person’s “people” and that grief therefore goes untended because people don’t trust the world they live in to hold them. He writes that grief;

is a time of natural molting, where the armor of rational thought is pulled away long enough to give us the necessary space of time, in which we are open and unhardened enough to let our new vulnerable state and its soft new skin surrender to grief’s able handling of the rudder of our little ship of sorrow and loss. For this reason, during these unarmored times of our lives we could be easily hurt by heartless people and the crassness of mindless situations. For this good reason we need other people, good people, to watch out for us on the everyday level, to listen and help us get through our grief times without having to be neither tough nor sane. These good people make sure we eat, stay warm, sleep, and don’t go doing things that are no good for anybody, but still keep things good for us, allowing us to say out loud what is needed even if it is weird or untrue.

I remember reading this and being extremely grateful that I didn’t feel lonely in my grief and that I knew without a doubt who my tribe were and who I could fall apart on. I hope that you all can find that sense of safety to be your vulnerable selves somewhere with someone.